“Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind; And therefore is wing'd Cupid painted blind. Nor hath love's mind of any judgment taste; Wings and no eyes figure unheedy haste: And therefore is love said to be a child, Because in choice he is so oft beguil'd.”

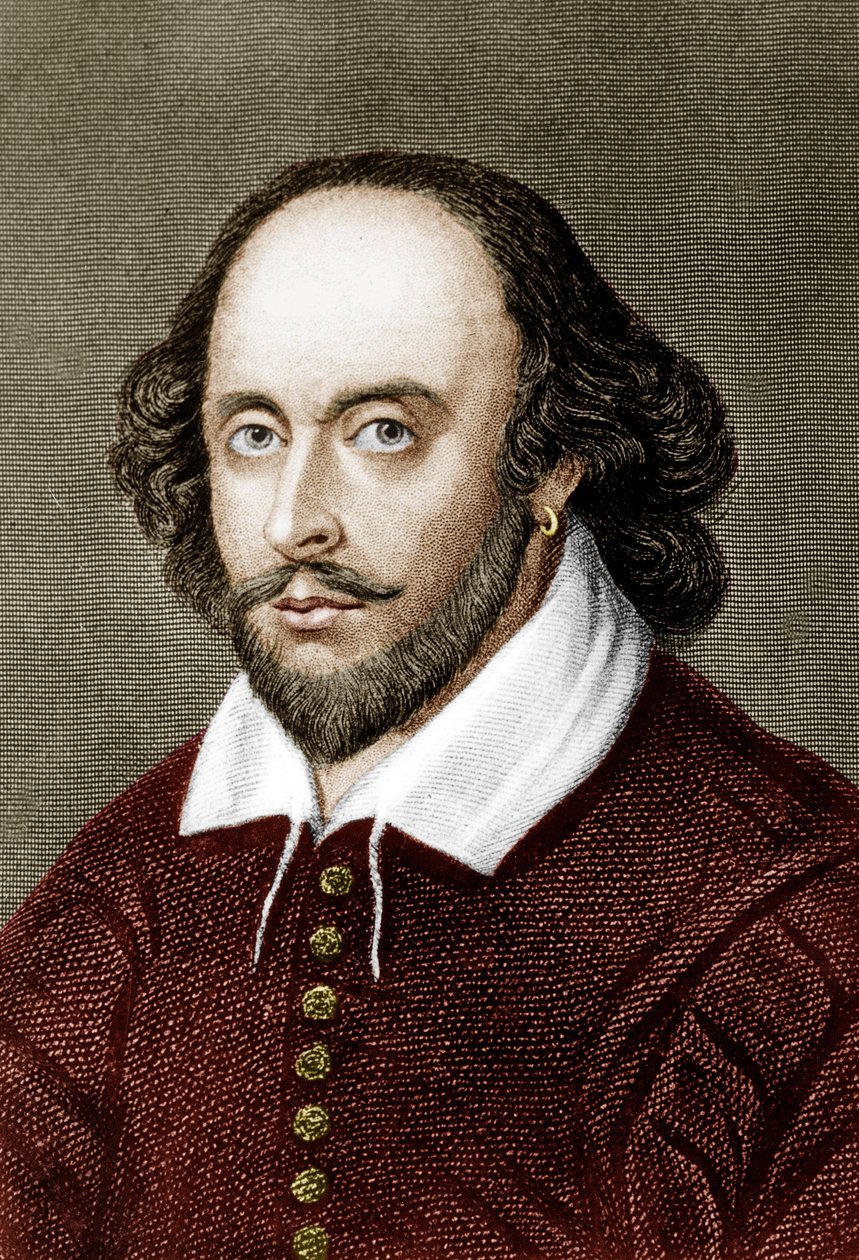

William Shakespeare

English playwright and poetWilliam Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” hitting stages in the 1590s, is a rowdy, radiant beast of a play. It’s a night-long tumble through a wood where love goes haywire, fairies meddle, and a donkey-headed fool steals the show. This isn’t just comedy, it’s Shakespeare thumbing his nose at order, weaving a tapestry of chaos that’s as sharp today as it was back then. Let’s crack it open, scene by scene, and wrestle with why it still grabs us by the collar.

The Gist: A Night of Tangled Hearts and Hooves

The story kicks off with Hermia, a spirited Athenian, defying her father Egeus and Theseus, Duke of Athens, who demand she wed Demetrius. She’s smitten with Lysander instead, and the two flee into the woods under moonlight. Hot on their heels is Demetrius, pursued in turn by Helena, who pines for him despite his indifference. “The course of true love never did run smooth,” Lysander quips (Act 1, Scene 1), and Shakespeare wastes no time proving him right.

The woods soon grow crowded. A troupe of “rude mechanicals”, working-class actors led by the irrepressible Nick Bottom, stumble in, rehearsing a play for Theseus’s wedding. Meanwhile, the fairy king Oberon and queen Titania, locked in their own spat, wield magic that upends everyone’s plans. Oberon, irked by Titania’s defiance, orders his trickster Puck to douse her eyes with a love potion, ensuring she’ll adore the first creature she sees. Puck, ever the imp, spreads the chaos further, enchanting Lysander and Demetrius and turning Bottom’s head into a donkey’s. When Titania awakens, she swoons over Bottom, cooing, “pluck the wings from painted butterflies / To fan the moonbeams from his sleeping eyes” (Act 3, Scene 1). What follows is a night of mistaken identities, broken hearts, and uproarious transformations.

Beneath the Laughs: Love, Power, and a Shattered Rulebook

At its core, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” revels in love’s absurdity. The potion symbolizes its capricious nature, driving characters to act against reason. Puck sums it up with glee: “Lord, what fools these mortals be!” (Act 3, Scene 2). Yet the play digs deeper, using magic to question control, over oneself, others, and society. The enchanted wood, lit by a moon “like a silver bow” (Act 1, Scene 1), becomes a playground where rules dissolve, exposing the fragility of authority and class.

Shakespeare’s Elizabethan audience would have recognized the jab at their own rigid hierarchies. The lovers defy patriarchal edicts, the mechanicals mock pompous nobility, and the fairies wield power no mortal can match. This social inversion feels almost revolutionary, cloaked in comedy’s forgiving embrace. Today, the play’s fluidity, especially in gender and desire, resonates anew. Modern staging often cast the lovers or fairies with queer undertones, highlighting how love defies boxes, then and now.

Isabella1400

https://shorturl.fm/K6ggb