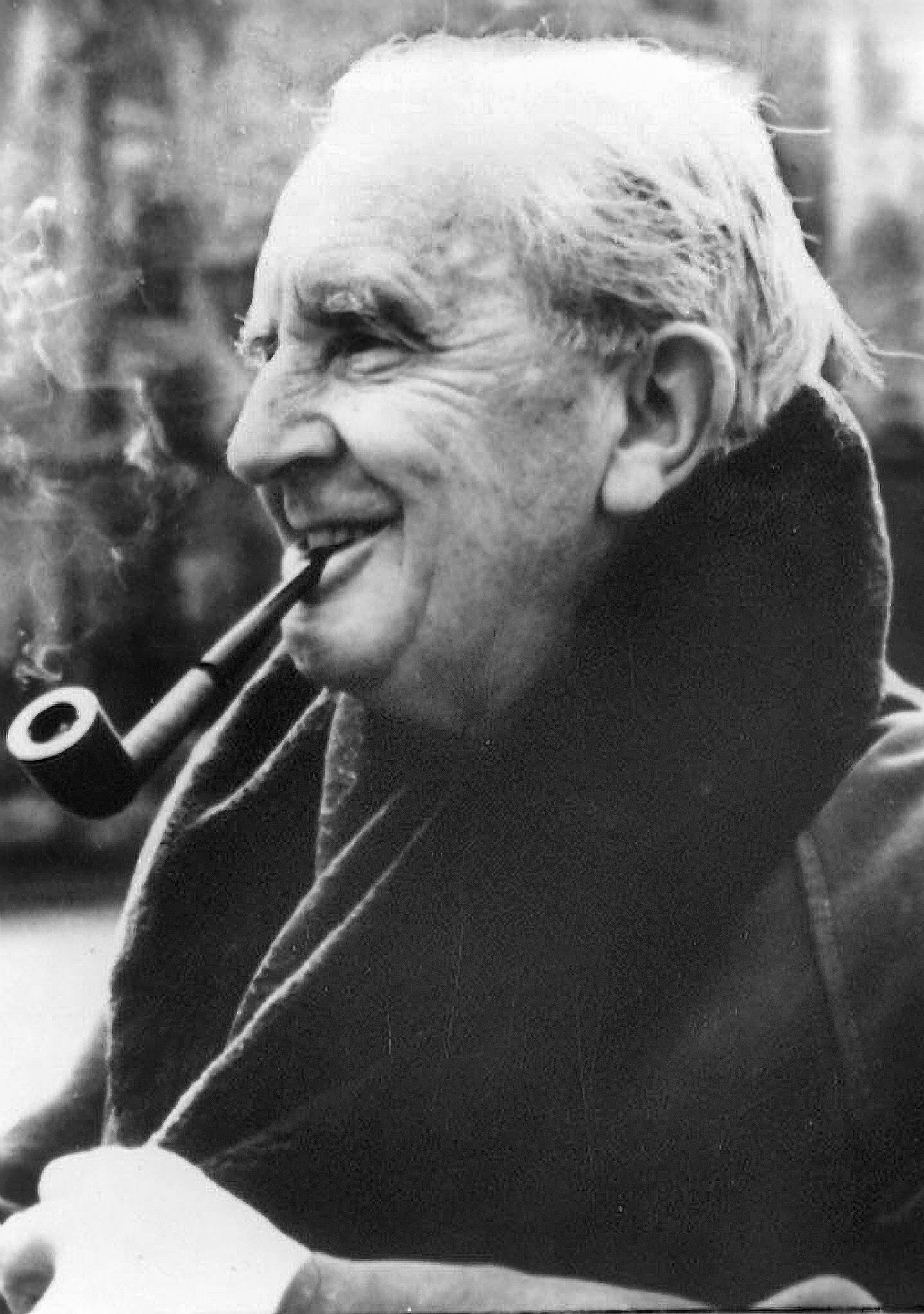

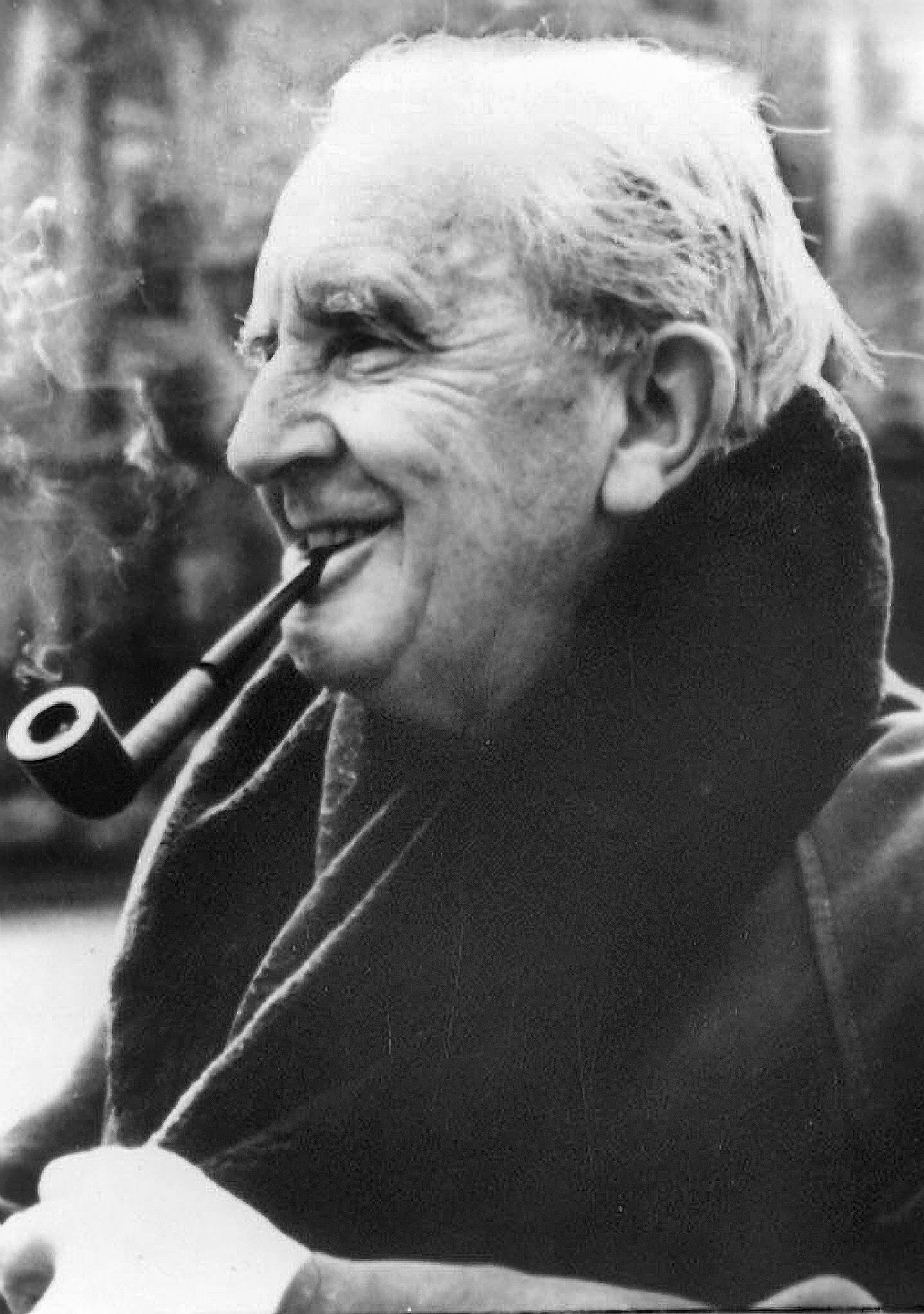

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Fellowship of the Ring“The world is indeed full of peril, and in it there are many dark places; but still there is much that is fair, and though in all lands love is now mingled with grief, it grows perhaps the greater.”

J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings stands as one of the most influential high-fantasy novels ever written, continuously shaping the genre while having set a precedent for modern fantasy literature. This series of books is often mistakenly considered a trilogy, when in fact, it is a single novel composed of six books, alongside extensive appendices. The publishing history of this influential work is filled with editorial challenges, unauthorized editions, and ongoing textual refinements, many of which were overseen by Tolkien himself and, later, by his son, Christopher Tolkien. The intricate evolution of The Lord of the Rings stands as a testament to its enduring literary and linguistic complexity.

The First Publication and Early Errors

The first volume, The Fellowship of the Ring, was published in the United Kingdom by George Allen & Unwin on July 29, 1954, with an American edition following on October 21 of the same year. From the outset, Tolkien faced challenges with printer’s errors and compositor’s alterations, which frequently disrupted his meticulously crafted linguistic expressions. The unauthorized alterations included changing dwarves to dwarfs, elvish to elfish, and, much to Tolkien’s frustration, elven to elfin.

I am extremely sensitive about my nomenclature, and much dislike editorial tampering, however well-intentioned.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

Writer and philologistGiven Tolkien’s expertise in philology and the intricate nature of his invented languages, such inconsistencies weren’t minor inconveniences but significant disruptions to the integrity of his world-building. The problem continued to persist across subsequent volumes, The Two Towers (published in 1954 in the UK and 1955 in the US) and The Return of the King (published in 1955 in the UK and 1956 in the US). Despite Tolkien’s best efforts to oversee corrections, many errors persisted, and new ones emerged with each printing.

The Abandoned Index and Publication Delays

One of the most significant editorial challenges arose in the third volume, The Return of the King. Tolkien had initially promised an extensive index of names and languages, which he worked on meticulously. However, due to its length and cost, the index was ultimately abandoned, and the publisher issued an apology for its absence. This decision led to delays in publication, further exacerbating the frustrations Tolkien faced in ensuring textual consistency.

The Unauthorized Ace Books Edition

In 1965, a major controversy erupted when Ace Books released an unauthorized paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings in the United States, bypassing copyright obligations and paying no royalties to Tolkien. To counteract this, Tolkien undertook a significant revision of the text for an authorized edition published by Ballantine Books later that year.

This revised edition saw changes not only in typographical errors but also in Tolkien’s own foreword, which he replaced entirely. The appendices, too, underwent extensive revisions. However, due to the rushed nature of this corrective effort, further inconsistencies and errors arose, creating multiple branches of textual descent that would take years to reconcile. “I much regret that so many minor errors still remain,” Tolkien admitted in a later letter. “Even now I continue to discover them.“

Christopher Tolkien’s Stewardship of the Text

Following Tolkien’s death in 1973, his son and literary executor, Christopher Tolkien, undertook the painstaking task of maintaining the textual integrity of The Lord of the Rings. In 1974, he submitted numerous corrections, primarily typographical, to Allen & Unwin for future editions.

However, the constant resetting of type for new editions, particularly in paperbacks published in the 1970s and 1980s, led to a proliferation of new errors. The British hardcover edition remained the most authoritative, but even it was not immune to inconsistencies. In the United States, Houghton Mifflin maintained the Ballantine edition’s text until 1987, when they adopted the updated British edition, incorporating Christopher Tolkien’s corrections.

The Digital Era: New Errors and Fixes

A major shift in the textual history of The Lord of the Rings occurred in 1994 when HarperCollins digitized the text for new editions. While this transition allowed for greater uniformity, it also introduced new errors. Some were minor, while others were more complex, such as the accidental omission of a line from the One Ring’s inscription in The Fellowship of the Ring or the inexplicable disappearance of the final sentences in The Council of Elrond.

Despite these setbacks, Christopher Tolkien continued to oversee revisions, ensuring that errors were gradually corrected in later printings. The 2002 three-volume edition, illustrated by Alan Lee, integrated additional corrections, further refining the text.

The Legacy of a Living Text

The textual evolution of The Lord of the Rings is unparalleled in modern literary history. Not only has the novel undergone meticulous revisions over decades, but its development has been extensively documented, offering a rare glimpse into the creative and editorial process of one of the greatest works of fantasy literature.

For those interested in exploring the complexities of its composition, Christopher Tolkien’s The History of Middle-earth provides an invaluable resource, detailing the novel’s transformation from its earliest drafts to its final form. Works such as J.R.R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography by Wayne G. Hammond and Douglas A. Anderson further illuminate the intricate publishing history of the text.

Tolkien himself once remarked on the difficulty of keeping revisions in order, lamenting the “constant breaking of threads” in his work. Yet, through the efforts of both father and son, The Lord of the Rings has maintained a textual integrity that few literary works can claim. Even now, more than seventy years after its initial publication, it remains a living text, scrutinized, corrected, and cherished by scholars and readers alike.